Just an ordinary day: you’re stuck in traffic, wondering if you’ll be late for your meeting, and your famous (former) best friend is flashing her blinding smile at you from a billboard, now a model-actress enticing you to buy into an aspirational lifestyle achievable with what she is selling, at the moment, and you think: “God, you are a bastard!”

So begins What It Means To Be Malaya by Emmily Magtalas-Rhodes, a blistering look at the advertising industry, the chaotic politics of childhood that never really leaves you, and being an ordinary girl in a world of beauty queens and superstars, daring the question: what does it really mean to be free in a world where God plays favorites?

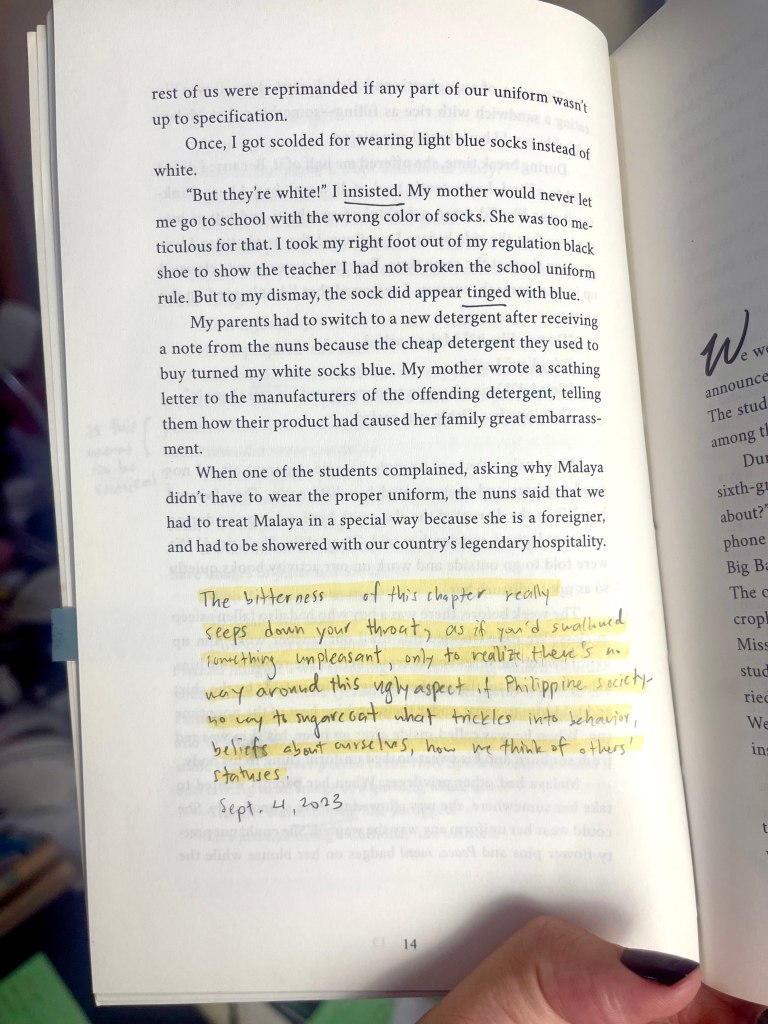

At the outset, Bunny sees loveliness as the key. She is now a grown-up writer for her local magazine. By all accounts, she was a good kid, intelligent, sensitive, empathic, with a poet’s soul, noticing everything wrong about Philippine society: the hypocrisy, the double standards, the reality of privilege and oppression, the not-so-subtle racism, and the many ways religion restricts, numbs, and hates on heathens.

Bunny also succumbs to spirals of envy, which opens the first chapter when she is haunted by her frenemy’s glare on a glossy fashion magazine, which she cannot avoid, and again when she reads of her adventures and sublime encounters with the world, who Bunny idealizes and encapsulates in her very name: Malaya.

By contrast, Bunny is anxious, quietly suffocated by her mother’s strict routines and schedule, still heavy with the weight of their childhood together in a school run by nuns. She and

Malaya exchange letters over the years, her body reacting before she does when Malaya relays her love story: “I gasped, breathless. It was too much for me. I had never been in love and I felt nauseous, like I was having a heart attack.” Bunny had never felt so close to God before, not even when she meticulously keeps a prayer journal in the attic with God’s responses to big asks, like “God, please give me a boyfriend,” but being up close with Malaya, her definition of beauty, of love, of freedom, of a life that seemingly resembles poetry, this was too much, to be in the presence of glory itself.

Beauty is painful, and the painful beauty of Malaya serves as her lens to look outward, beyond what is possible, and beyond what she is told to do. With the claustrophobia of The Bell Jar and the humor of The Devil Wears Prada, this book is a perfect meditation on what it means to be a woman in the 21st century Philippines mired by colonial beauty standards and aspirational capitalism.

Leave a comment